Artist Talk: Photographer Sara Bennett profiles women who are, or were, incarcerated

Tuesday, October 17th, 2023

Sara Bennett didn’t start her history with the American judicial system as a photographer.

She began as a public defender.

But it was what she experienced in that role, and the contacts that she’s made with formerly incarcerated women, that bridge that transition. Those experiences form the lens — both literally and figuratively — of her body of work today. Her work has been exhibited in museum shows including in the Blanton Museum of Art’s Day Jobs, MoMA PS1’s Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration and the Museum of the City of New York’s New York Now: Home, and in solo shows, including at the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon, Photoville in Brooklyn, New York, and Rotterdam Photo 2023. Her work has been featured in such publications as The New York Times, The New Yorker Photo Booth, and Variety & Rolling Stone’s American (In)Justice.

Bennett will deliver an Artist Talk at PCA&D Thursday, Oct. 19, at 12:30 pm in the Atrium. The event is free and open to both the College community and the public.

Learn more about her inspiration, the goal of her photography, and what she’s learned by making art:

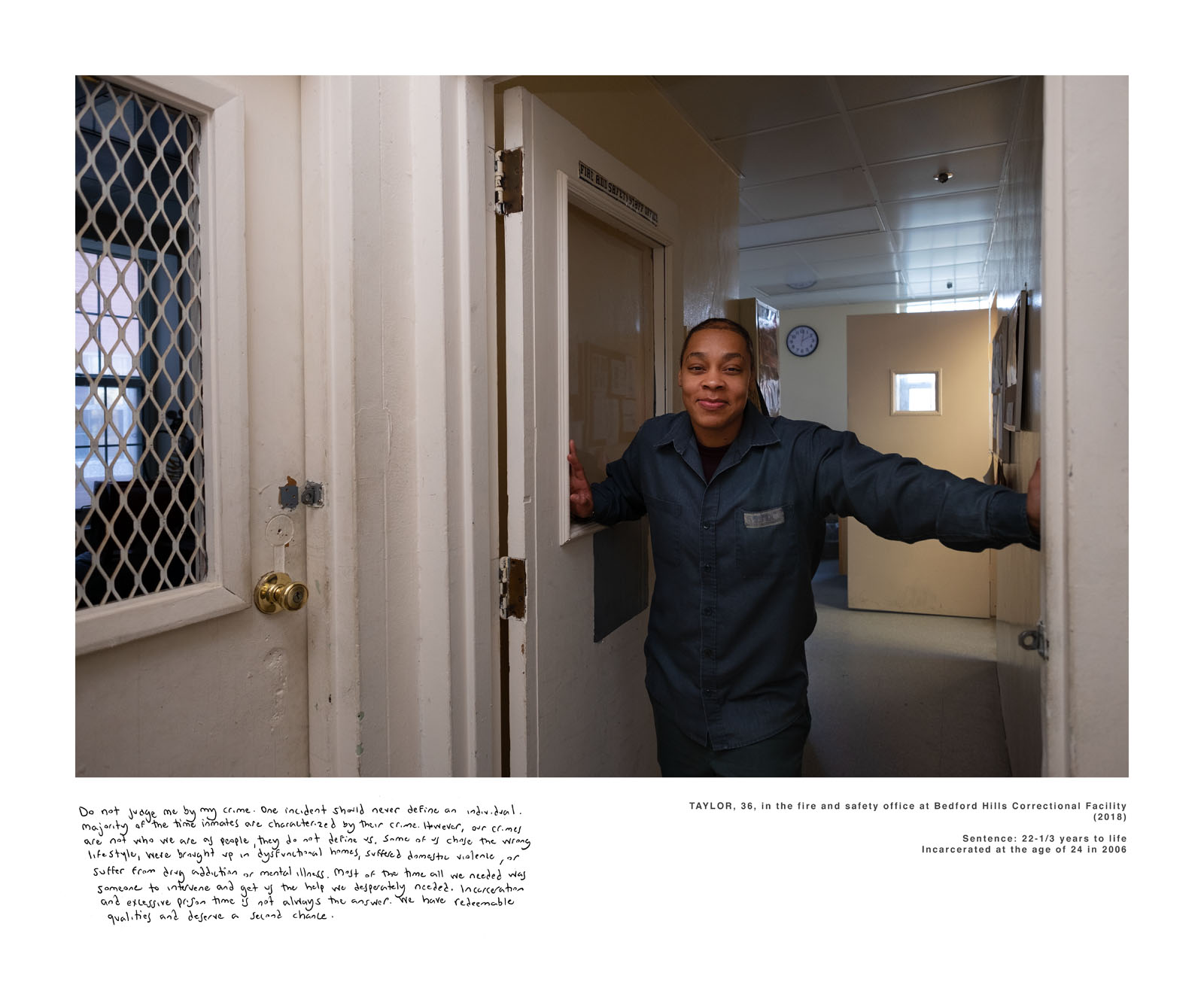

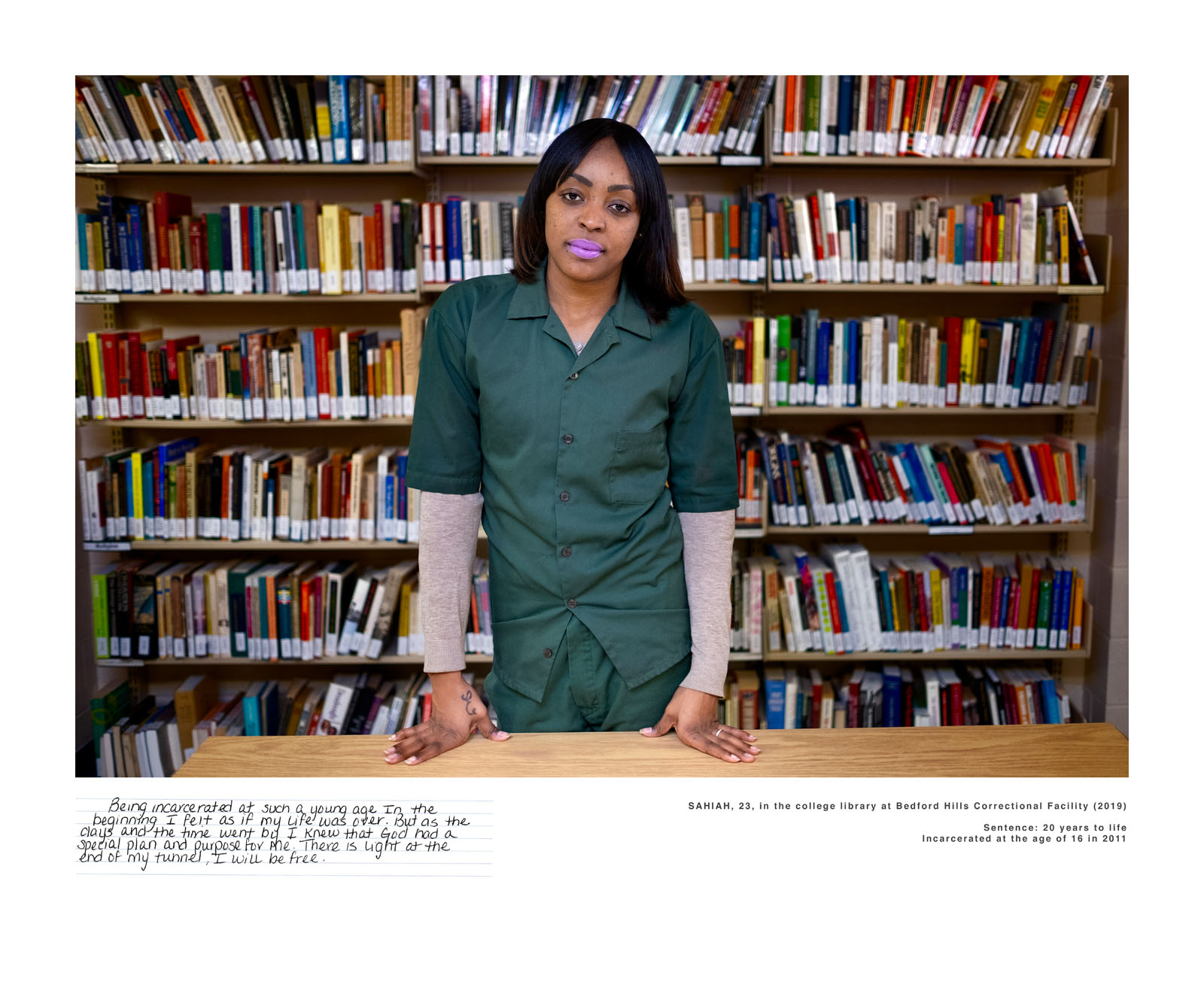

Photos by Sara Bennett

Was there a specific person’s story that led you to make the transition from public defender to photographer? I’ve read that it was Judith Clark?

Sara Bennett: After an 18-year career as a public defender, I left the practice of law in the mid-2000s to pursue other interests. Over the years, I had developed close relationships with some of my clients and in 2009, some of the formerly incarcerated women I knew beseeched me to take on the case of Judith Clark (Judy), a woman who had been in prison for 28 years and would die there unless I could persuade the governor to grant her clemency. I became her pro bono attorney and I tried everything I could think of to show that she was an extraordinary person, worthy of the governor’s mercy. I even created an audio recording of famous actors reading from letters of support to try to capture the interest of the governor at that time, who was blind.

When the next governor came into power, I tried something new. Although I hadn’t picked up a camera in decades, I thought I would try to humanize Judy by taking portraits of women who had been incarcerated with her and have them write about her influence on their lives. I created an advocacy book, “Spirit on the Inside: Reflections on Doing Time With Judith Clark”, and sent it to the then newly formed Commission on Re-Entry, as well as state legislators, the governor, and others with political sway.

What was the impact of that book?

SB: Anyone who saw the book was surprised at the seeming “ordinariness” of the formerly incarcerated women and curious about their life stories. That reaction made me realize not only how little the general public knew or thought about people behind bars, but also the power of photography as an advocacy tool. I have now been on a ten-year path of chronicling New York State women with life sentences, both inside and outside prison. All the women I photograph have been convicted of homicide.

As an attorney, I had specialized in representing women who had killed their abusers and so I made the very conscious decision to focus my lens on women convicted of violent crimes and sentenced to life in prison, with or without the possibility of parole. I wanted to draw attention to this even more hidden group and advocate against prisons as we know them.

What is your goal with your photography?

SB: My goal in all of my photography work is to show the humanity in people who are, or were, incarcerated. Including the women’s handwriting emphasizes that these are their words, these are their thoughts. I’m convinced that if judges, prosecutors, and legislators could see people sentenced to life imprisonment as real individuals, they would rethink policies that lock them away forever.

I had incredible access to the world of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women through my work as a criminal defense attorney. A lot of the women knew of me through their friends or peers who I had represented. The first day I met and photographed Keila, who was referred to me by my client, Judith Clark, she took me to a meeting of formerly incarcerated women. When I walked into the room, I knew a few of the women and when I told them my ideas for a re-entry series, every single woman wanted to be part of the project. So on day one, I suddenly had more than a dozen potential women to photograph.

What have these projects taught you about the system which you’re reflecting, our system of justice and incarceration? Is that a different lesson than you learned in law school?

SB: Because I had been a defense attorney for so many years, and because I had strong relationships with many of the women I had represented, I already had strong feelings about what was wrong with the system and what I wanted to say about it. Through my photography, though, I have learned a lot more about daily life inside prison and the challenges of re-entering society after decades behind bars.

Learn more

Photo of Sara Bennett: Credit Cory Rice, cory-rice.com