Eric Dyer’s zoetropes are the models of a modern motion artifact

. . .

Thursday, November 4th, 2021

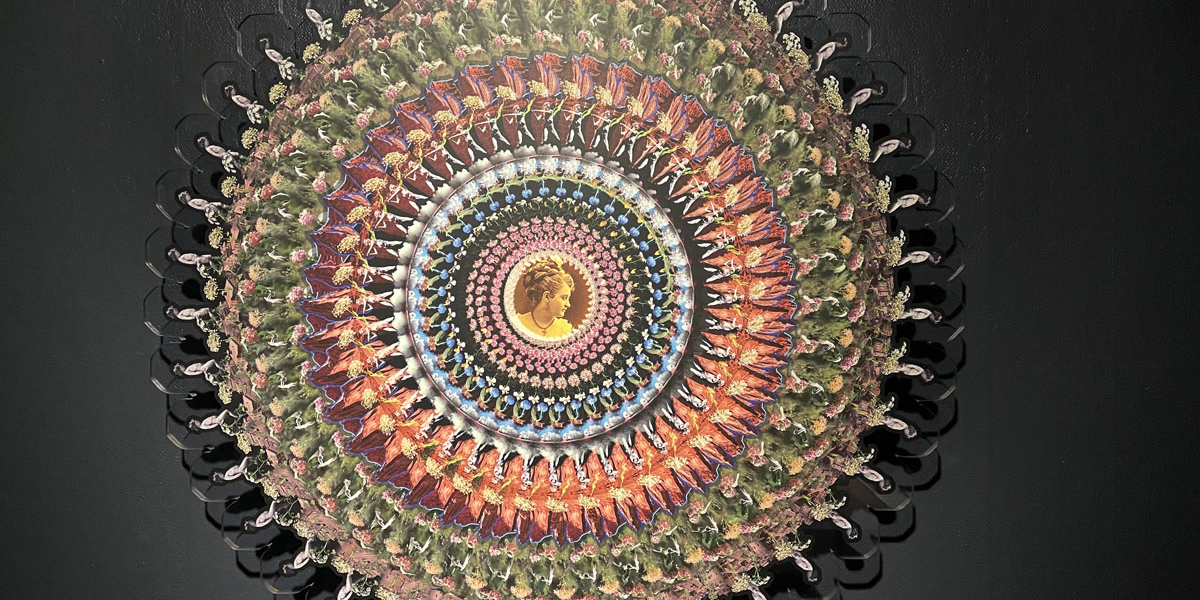

Modern art sometimes relies on cutting-edge technology to make its point, but artist Eric Dyer turns photos, 3-D objects, and kinetic sculpture into a modern reimagining of a 19th-century optical device:

His zoetropes pull art into a physical 4th dimension, he says, counterbalancing the virtual, screen-filled world that surrounds our 21st-century lives.

“As the material, sensorial, physically present communal human experience is diminished,” Dyer says, “a void is left that this form of art helps fill.”

Dyer’s Pulse and Flow: Art of the Modern Zoetrope opens Friday, Nov. 12 in the Gallery at PCA&D, and will remain on exhibit through Jan. 12, 2022. We talked to the University of Maryland, Baltimore County professor, filmmaker, photographer, sculptor, and former professional animator about his workflow, how he collects the images and ideas which find their way into his zoetrope creations, his dream collaborators, and more:

Your work encompasses so many media and techniques — sculpture to zoetrope to drone to computer animation, to 3D printing… and so much more. When you’re starting a piece, do you have in mind everything you will be using, or does the piece sort of unfold as it develops?

Eric Dyer: In the zoetrope lies the key to unlocking the 4th dimension of nearly any medium or technique. Motion pictures are ubiquitous, but particularly with animation, the original medium (i.e. clay, drawings, paintings, ready-made objects, etc.) must be “converted” to the immaterial projected image or flat, slick screen. The modernized zoetrope is a motion artifact that allows animated art to retain its medium. In zoetropic paintings we see the actual and honest color and texture of the brushstrokes come to life, animated shotgun shells are exactly that, and the same is true for nails and yarn, etc. Witnessing these physically present mediums/objects come to animated life situates viewers in a kind of uncanny valley between reality and fantasy — the mediums are real and familiar while their motion feels impossible. Circling back to your question, I’m not in the driver’s seat — it’s the possessed subconscious that decides what will be explored next, and the processes have often been chaotic in practice, as so much of what I’m creating has little to no precedence. The journey is full of experimentation, a maze of dead-ends, U-turns, and numerous possible routes to the destination (final artwork).

“Pulse and Flow: Art of the Modern ZoetropeEric DyerNovember 12, 2021 through January 12, 2022The Gallery at PCA&D

Do you feel viewers react to your work differently than if it would be screen-based animation? How so?

ED: Absolutely, for the reasons above, and also — my creative path showed me the difference first-hand, as I previously made zoetropic sculptures to make films. At film festivals, audiences were fascinated by the process and wanted to see the sculptures that created what they saw on the screen. I began exhibiting the zoetropes as installed art, and thereby witnessed a profound increase in the public’s engagement with the work. Perhaps this is because we are very much used to the fabricated realities in film and video but not as something that occupies a bodily shared space and time. Beyond that, the developed world has very recently experienced a dramatic shift. Work, play, and socializing had formerly involved our bodies in motion, our collected senses, and our physical presence. Today these activities are often accomplished remotely, virtually, and with our nearly static selves, seated and/or staring at screens. Just as film was the medium to fit the rocketing pace of the early 20th century, zoetropic art fits, or maybe counterbalances, our modern times — as the material, sensorial, physically present communal human experience is diminished, a void is left that this form of art helps fill.

Do you often reach back into your own archives for photos or video you shot long ago to incorporate into new projects? Or do you start each work with a blank slate?

ED: Over time I have learned that shooting video “just for fun,” just because I find the subject or motion or imagery or event interesting, may seem to have no use in my art practice, can later become brilliantly useful to a future project. For example, in 2014 I taught a workshop in Shanghai. In my free time, I shot video of interesting kinetic moments throughout the city. Noticing the prevalent use of umbrellas and parasols, I asked my students to bring their favorite “bumbershoots” to class and perform various motions for the camera. I had no idea what I would use the footage for and the clips sat in a folder for months. While beginning the “Shabamanetica” project months later, I visited the Baltimore Museum of Industry and learned that Baltimore was once the umbrella-manufacturing capital of the world, an industry that died when cheap goods began flooding in from China. These findings added depth to the project — it became a rumination about industrial heydays: the “first-world’s” past trades and China’s young and blossoming industries — and made footage I’d shot years before in Shanghai essential. And it’s quite possible that the umbrella display at the industry museum would not have grabbed my attention if I had not playfully engaged with umbrellas in Shanghai.

If you could collaborate with another artist, who would your dream collaborator be?

ED: I’m drawn to the work of certain contemporary electronic music artists/composers out of the UK: Rival Consoles, Max Cooper, Jon Hopkins, and Richard James (the demigod of the genre). The looping motion of zoetropic art shares some common ground with electronic music sequencing. I’ve casually imagined an exhibition of music and sculptural animation synchronized together, the visual art and musical art created out of nonverbal back-and-forth “conversations” between collaborators — quite possibly an engaging and fulfilling creative experiment.

What skill are you teaching yourself now?

ED: To make work nonverbally/non-linguistically (external and internal voice alike). Language is largely handled by the logical/intellectual/

I’d also like to learn how to use a lathe.

image: “Red Hulls,” Eric Dyer