‘Look badass’ is the most common design request: Zak Keller of Atomic Design

Tuesday, March 2nd, 2021

Zak Keller has been earning paychecks in show biz for the past 23 years. In that time, he’s been a Technical Designer, Art Director, Set Designer, Audio Engineer, Production Manager, Video Designer, Carpenter, Prop Master, and Charge Artist for hundreds of productions ranging from theater, opera, musicals, dance, episodic television, touring concerts, music festivals, sports, and awards shows, in addition to top-secret product launches, trade shows, and professional wrestling. He fuels his creative energy by being the guy that figures out how to make it happen, on time and under budget … or at least on time.

On March 4, Keller joins the College as the inaugural speaker for our Live Experience Design BFA program, a new PCA&D major now under accreditation review.

For the last nine years, he has been a Senior Project Manager at Atomic Design Inc. and enjoys tremendously diverse work making scenery primarily for TV, music, and live events. That may involve creating designs from scratch with only conversation to guide him, collaborating with outside designers on moderately defined designs, or executing a client’s fully detailed design. He also enjoyed a four-year stint as a Professor of Design in Theatre and has found a great deal of satisfaction getting former students employed whenever possible. Zak holds a BA from the University of Northern Colorado and an MFA from Pennsylvania State University, both in Theatrical Design.

His latest project is the co-construction of a strong woman named Madison Aria Keller (born Feb. 15, by his wife, Ada). This particular project, Keller says, “is likely to exceed budget expectations.”

In between feedings, naps, and admiring Madison Aria, Keller was kind enough to answer a few questions for PCA&D:

Your LinkedIn bio describes your job as equal parts technical designer, art director, roadie, and workflow wrangler. What skills have been important to develop so you can handle all these demands simultaneously?

ZK: First and foremost: flexibility! With large projects, it can be exceedingly difficult to reconcile technical needs, aesthetic goals, stakeholder emotions, and budgetary/calendar constraints. As the primary accountable person to a show loading in on time, it’s important to realize that it’s almost always impossible to navigate these hurdles with 100% success. Be malleable to prioritize the hottest fire, but give yourself the grace to change that priority as needed. Don’t fall into the fallacy of sunk cost, and don’t spin your wheels failing to multitask. If a design idea is taking ever more mental acrobatics to justify, walk away and start fresh. Everything is easier to draw the second time.

In my personal background, a wide variety of technical jobs to pay the bills through high school, college and grad school grounded me in the world of the achievable. My formal arts education allows me to motivate that baseline practicality to ruthlessly execute the creative vision of others. I dislike few things in life more than compromising inspired design just because of pesky things like physics. Whether I am leading the design directive at a top level or seeing someone else’s vision through to fruition, I always want the technical solutions to invisibly enable the aesthetic goals.

When it comes to wrangling workflow, practice makes perfect. Knowing how many steps ahead to be focused on to maximize productivity across a group is an art form all its own. Workflow is also quite varied across diverse units and environments. Talking with modeling and drafting teams through how to construct a piece that loads in three times a week — for years — requires a totally different tenor than leading 40 stagehands building a nine-story set piece for a one-night-only. While all of this sounds fundamentally collaborative, you are always a moment away from needing to put your foot down and be decisive, even if it’s an unhappy compromise.

“If a design idea is taking ever more mental acrobatics to justify, walk away and start fresh. Everything is easier to draw the second time.”

— Zak Keller

With your background in theater, what was the most challenging transition to the kind of live entertainment design you do now?

ZK: I will never cease to be amazed by the places that consider themselves to be backstage, from the White House to the muddy field of a music festival. Jargon certainly varies at convention centers, stadiums, TV studios, and opera houses. However, the communal paradigm of an impending opening night fosters rapid camaraderie amongst all production types. Those who don’t enjoy that paradigm weed themselves out of the industry quickly. As such, it’s a shockingly small group of leaders within such a large industry.

That said, at Atomic, we serve an extremely diverse client base. On Sunday I can be dangling from the end of a crane getting a stadium-sized piece dialed in with a bunch of roadies. On Monday I may be on a conference call with executives trying to decide between 80% and 82% gray carpet for their keynote. I really like to avoid shapeshifting, because I’ve met far too many people who seem insincere in most professional settings as they try to fit in with all. It’s taken a long time, but I’ve gotten comfortable being a little too rough for the executives and a little too straitlaced for the ironworkers.

The most fundamental difference of the design work itself is a lack of playscript analysis or necessary literary critique. That makes for a very broad canvas, something that may annoy a lot of stage designers. Lots of clients can be visually illiterate people. “Look badass” is almost certainly the most common design brief I get. If I’m uninspired by a script, say for a Chekhov play, I can always fall back on a literal interpretation of the script’s needs. While that happens in some of my TV work, it’s rare. If I’m not feeling inspired by a client’s concept, the burden to make it good is squarely on my shoulders. I’m exceptionally fortunate to be surrounded by teams of creative people who can craft engaging design from very little directive. The flip of that is that lots of my clients are insanely good at design and communicate their priorities perfectly. In those situations I am much more like a theatrical Technical Director, enacting a vision with as few compromises as possible. The pendulum swinging between those experiences is surprisingly rejuvenating.

“ ‘Look badass’ is almost certainly the most common design brief I get.”

— Zak Keller

For someone who’s entering your field from a purely design background, what’s important to keep in mind? What would be important experience or knowledge to add to their resume?

ZK: Be willing to jump into the middle of conversations. Nobody ever got a deserved promotion by staying away from the room where decisions get made. You don’t need to run the conversation, but do whatever you can to get as deep into the information flow as you can without overstepping your welcome or shortchanging your other responsibilities.

Be engaged in details. At first, knowing which details matter is really hard, and that’s OK. Take the time to critique your work. Be your toughest critic. Speak up as soon as you realize a problem exists, especially if you’re the only one who can possibly know. Nearly all of my professional failures stem from not listening to that little voice that says calamity is approaching. Always be the first to own your mistakes or missteps. I like to say that half my job description is accepting blame. It’s easier to rejoice in success when you hold yourself accountable for your shortcomings. Your team will respect ownership of less than ideal choices over shoulder shrugs. Your clients simply won’t return for shoulder shrugs.

As far as resume, it can be painfully slow to build a meaningful work history that will land gigs. The worst irony is, by the time you really feel like you get there, you’ll almost never need your resume. As such, the most common advice I find myself giving is: Be proud of your skills. Even if a student has little practical experience, they have skills. Give yourself due credit. A potential employer won’t know you know how to solder or program or embroider or blacksmith if you don’t tell them. Even if the skills aren’t directly applicable, having a robust skillset list says more than an “I’m happy to be here” of listing class projects.

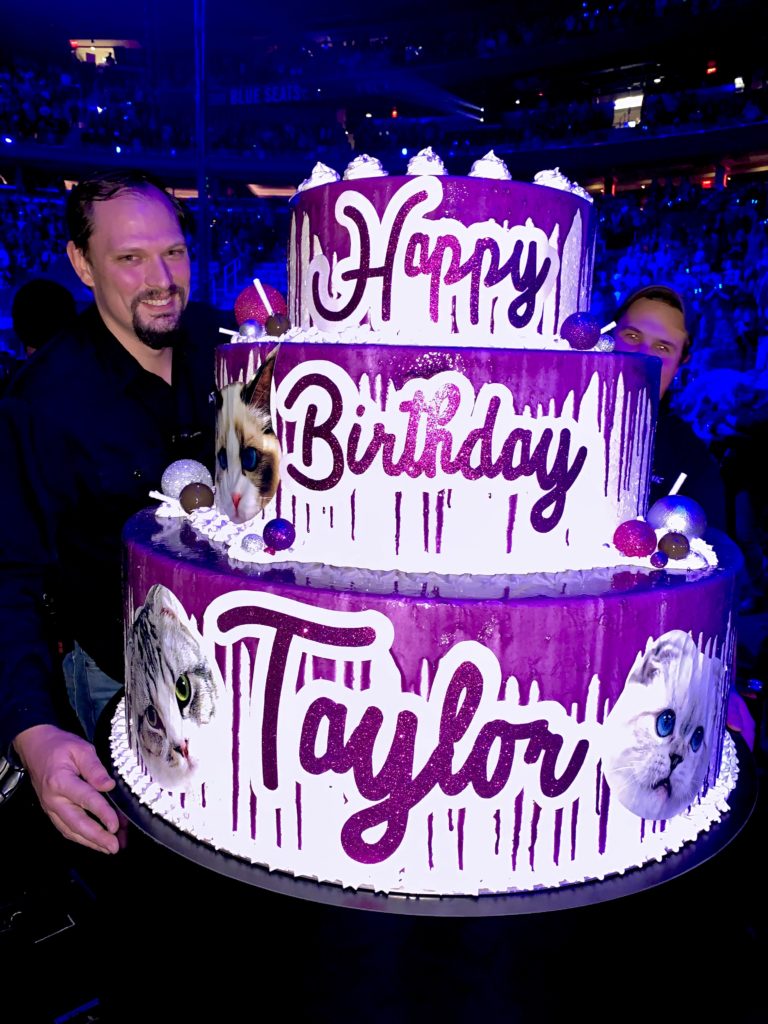

Atomic Design in action

And, finally: As live entertainment works its way back after the past year of pandemic challenges, do you have any suggestions based on that experience to share with our students?

ZK: Perseverance, a willingness to pivot, and dedication to your savings account. While this past year has been difficult for everyone, I will never equate the devastation of losing livelihoods to all those who lost their lives or loved ones. Thankfully we have a really dedicated talent base who are eagerly waiting for science to get us all back in stadiums, at concerts, and live events. Brain-drain has been a concern as those close to retirement age or burnout have hung it up for good. That said, I am optimistic that the next 24 months will offer great opportunities. Students just entering the workforce will see a flurry of work that has been backlogged. Employers will be eager to hire back up to pre-pandemic levels, especially those who will see $30-40k as a welcome breath of fresh air compared to piling on more student loans.

Start making and maintaining personal connections to potential employers ASAP. Let them know your long-term goals while understanding that they may not be hiring yet, though a handful certainly are. Start with the HR person or department if you have to, but really try to get in direct contact with the people in the department that you are interested in. HR departments are awesome, but one of their purposes is to keep the workforce from being inundated with resumes. As such they don’t always know a great candidate when they see one. Fake (or real) capstone research projects are great for end-running this if you have no other inroads with your ideal employer. It certainly takes a lot more effort, but a 15-minute phone interview gets your foot wedged in the door in a way that isn’t dripping in self-promotion. Follow up with them with excerpts of your class project (real or invented). Don’t be afraid to lean on the networks of your faculty and graduated classmates.

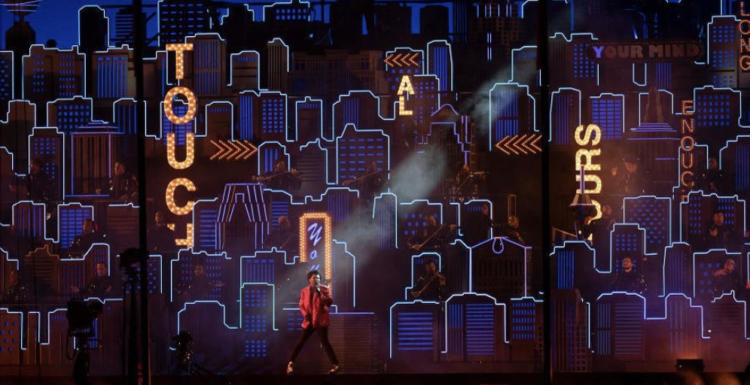

Top photo: The Weeknd performs at the halftime show of Super Bowl LV, in February 2021. Photo courtesy CBS.