Faculty member Adam DelMarcelle uses ‘Mariah’ app to turn augmented reality into activism

Tuesday, December 15th, 2020

For years, the Sackler family has been a player in the world of global art philanthropy. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art has a Sackler Wing; so does the Louvre in Paris. England’s University of Oxford has a Sackler Library, and the Guggenheim has a Sackler Center for Arts Education.

But the art world has been embroiled in a debate over whether that Sackler name should remain etched into building facades, or whether institutions should accept Sackler donations at all.

That’s because the Sackler family, in its role as owners of Purdue Pharma, was behind the development, production, and promotion of the narcotic pain reliever OxyContin. In several lawsuits, including at the federal level last month, Purdue has admitted it deliberately misled the federal Drug Enforcement Administration about its highly addictive opioid medicines.

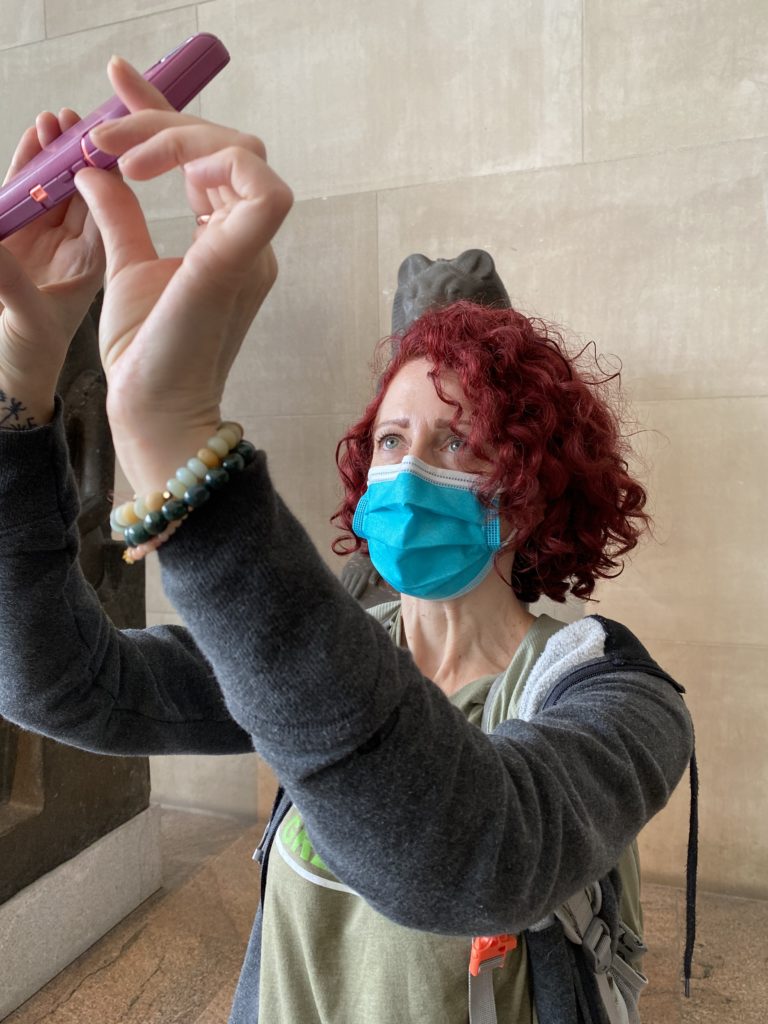

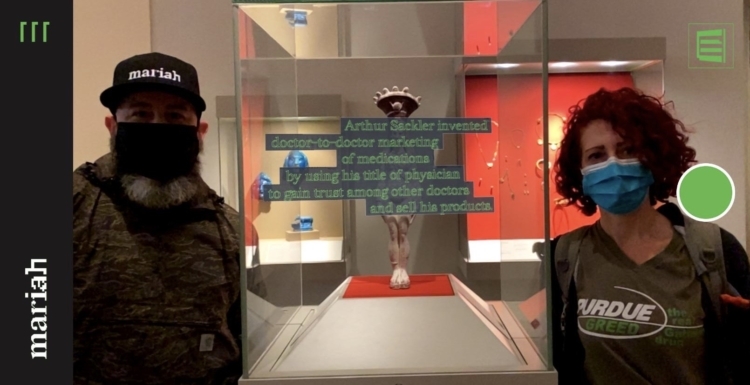

Now, a collaboration of art and technology, the Mariah smartphone app, aims to erase the line that divides the “good” results of Sackler money from the way in which it was earned. It’s a collaboration between Adam DelMarcelle, an adjunct instructor in PCA&D’s Graphic Design Department, and artist Heather Snyder-Quinn, an assistant professor of design at DePaul University.

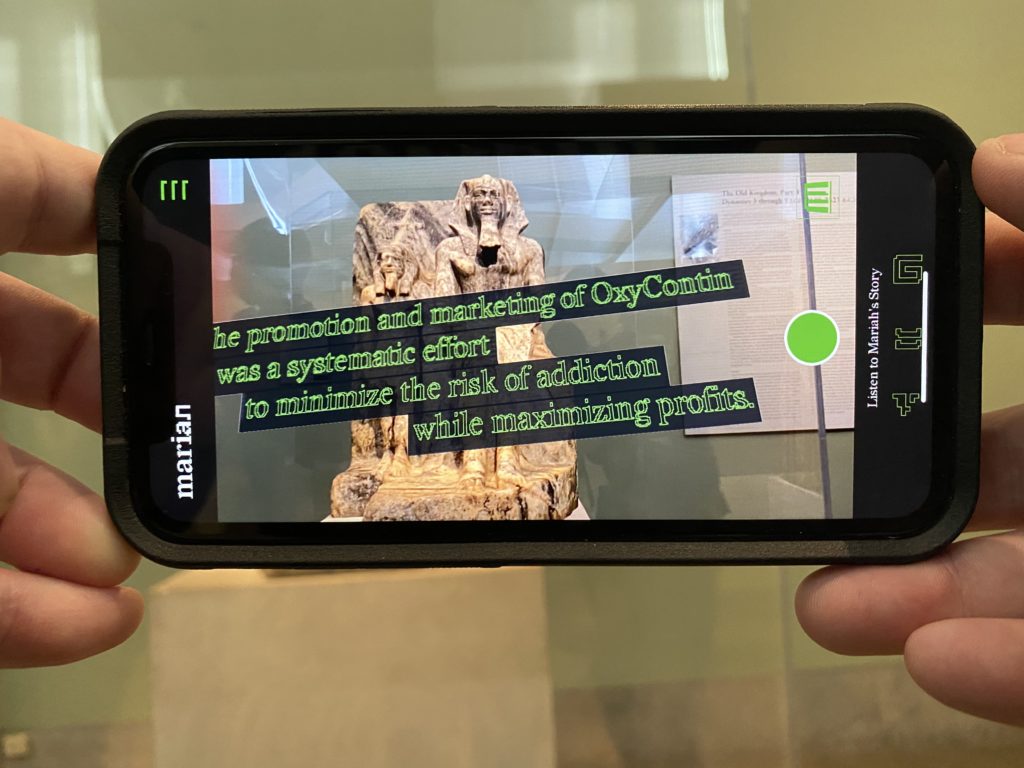

The Mariah app in use in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Sackler Wing, at the Temple of Dendur. Photo courtesy Adam DelMarcelle.

Here’s how it works: Point your smartphone at one of the priceless works of art in the Met’s Sackler Gallery and an image of Mariah Lotti may appear on the screen instead, blocking your view of the Temple of Dendur. Then you see and hear the words: facts about Mariah’s life, or her mother’s voice talking about Mariah’s addiction to a drug that, because it is prescribed by doctors, they assumed would be safe.

Here, the Mariah app implies: Here is the real price of that artwork. While the Sackler family has had its name carved in marble, the money behind that philanthropy has a legacy of pain.

The project is making waves, featured by both The Washington Post and Hyperallergic, among other media outlets.

For DelMarcelle, an adjunct instructor in PCA&D’s Graphic Design Department, the project is just the latest in a series of works that have focused on the opioid crisis — not just those who have profited from it, but also those who have lost their lives to it. Since losing his brother Joe to a heroin overdose, DelMarcelle has begun What Heroin Sounds Like, a project that melds art with community activism. Starting with posters in his hometown of Lebanon, Pa., and graduating to projecting images on buildings, and gallery exhibitions, DelMarcelle continues to bear witness to the impact of opioid drugs.

And he doesn’t see an end to this line of work anytime soon.

Your background is in Graphic Design. And the focus of your practice on opioids and their impact isn’t new — but this medium is. How did this idea for Mariah, in this augmented-reality medium, evolve?

ADM: For me, it is about finding diverse ways to tell the same stories. It is the teacher in me that needs to offer the information in varying manners that allows the information to be disseminated and hopefully understood by as many people as possible. The mediums I use evolve when the need arises for them to do so. When the prints were destroyed by the police by order of our (Lebanon) mayor, I pivoted to large-scale building projections. The projections were limited to the night. So next came museum exhibitions, which I only allowed to happen if the institutions conducted extensive community outreach along with the art. The art means nothing if it does not rise above the content. The work is just a vehicle to drive a message.

From here, it was about putting the work in place in a manner that reclaims space and can never be taken down. Augmented reality made that idea come to fruition. I am multidisciplinary because this allows me to pivot the status quo, keeping me dangerous and helpful. As John Lewis has said, “good trouble.” Collaboration allows you to have unlimited skill sets to throw at a problem.

Text from the Mariah app is superimposed over ancient artwork in NYC’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo courtesy Adam DelMarcelle.

Was Mariah always a collaboration between you and Heather Snyder-Quinn, or did one of you begin and bring the other on board?

ADM: This project was as pure a collaboration as could be initiated. We both were integral in each stage of developing this concept into the art action it currently is. Heather is very interested in the democracy of smart technology and privacy as it pertains to the digital realm. I am very interested in adding to the activists’ tool chest — finding ways in which to hack into the system to tell more earnest stories of the American narrative. Heather helped me to harness the power of emerging tech and I helped her to feel OK about getting into trouble for something you believe in. It reminds me of the political prints created by the Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico. They worked together to create the prints they produced. (For example), if I was not proficient at rendering hands, then one of the other artists did this portion of the work…if animals were not my strong suit, then someone else would do this. In the end they had perfect images talking about a specific issue (in most cases antifascism), and this is all that mattered: Making work that raises up injustice and speaks clearly. A signature on the bottom of a work of political art means nothing. (In a 1962 speech, author) James Baldwin tells us that our pain is trivial insofar as we can use this to connect to everyone else alive.

What is it about Mariah Lotti that made her story come to stand as the project’s namesake?

ADM: Mariah is just one story, but this is where the power of content-driven art and design breathes — one story at a time is where power lives. She died in America due to an epidemic of substance use disorder that is taking those we love far too soon. This is where this part of her story ends; the rest is of a kid that was immensely intelligent. She was a fierce guardian of her friends, an avid reader, and a lover of knowledge. She was a good daughter and sister. Mariah had plans, she had dreams, and she was human.

But she was also preyed upon by a capitalist system that places profit above life. She was hunted by opportunists that have one goal…sell, sell, sell….repeat. This system never sleeps and has a singular focus; how much can we make and fuck those that step in our way. These individuals rule in highrise cathedrals in every city in America. Big Pharma and its political strongholds enhanced by payoffs and political support caused this epidemic. In 1971, Richard Nixon’s war on drugs laid this foundation which has continued until present day. A war on its own people…a war that cost a trillion dollars…war that has incarcerated far too many…a war of class, a war started to decimate communities of color, a failed war that we have paid. for. Remember this: The government of this country does not care if you use drugs, they care who you buy them from. This system murdered Mariah. Mariah is the witness that represents all those preyed upon by this corrupt system.

How do you see Mariah amplifying the conversation and awareness around opioids?

ADM: Each new work allows the narrative to continue, and this is all that matters. This work is designed to allow people to ask themselves what part of the landscape of this issue are they responsible for and know … what will they be prepared to do. Inaction is not a choice. As Americans we are all responsible for the current state of the addiction epidemic crippling our country and we must all be responsible for changing, or at least asking better questions of ourselves. Why do we consume as much as we do? What is the price of our consumption? And who besides ourselves does it affect? If we allow our search to be open, we will discover the ripples of our individual trauma travel significantly further than our story. Many people have suffered for our consumption far beyond our American backyards.

Was there a specific process you used to match people’s stories to objects in the Sackler Wing?

ADM: At the Met we are only telling the story of Mariah and, in the background, the story of the Sackler family and their history of developing over decades a method of advertising and marketing their products to a public (that did not understand) the potency and danger of these medications marketed as therapeutic and safe. The frame these stories sit inside of is the Metropolitan Museum of Art that for over 50 years accepted money from this family and allowed them to artwash their sinister history. Much of the money given to this institution was made on the backs of the working class of America and much of this capital was obtained by the killing of others. When you think of the haves and the have-nots, understand that the have-nots killed themselves so that Rockefellers could donate a $50 million painting in their (own) name. Where is Mariah’s name? This is the question we asked and this is the history we corrected.

What was your process for capturing all the images needed in and of the Met? Obviously, the institution wasn’t an official part of Mariah, so were these photos taken “on the sly?” Was special equipment used on site?

ADM: A year ago my wife and I walked the Met and conceived the original experience (we hid in plain sight amongst the crowd taking pictures and my wife taking notes), which grew when Heather and I started to develop the idea and make it more complex. We walked through the crowd and subversively gathered the material we needed to hack the Met. There are different methods of placing AR (augmented reality) into the physical space: trigger images, GPS, and ground plane technology. We utilized a few of these to pull off the experience. Heather had experience placing AR in books and some outdoor locations, so we built on her experience to push the boundaries further. This included us doing extensive research into the legal aspects of what we were doing … Heather was integral in this process. If it was up to me we would have just jumped in and did it but thankfully Heather is more cautious, which allowed us to learn so much more deeply about the work we were doing and added a level of understanding and agency.

This project wouldn’t have been possible even a few years ago. Can you imagine next steps that you’d like to pursue as technology evolves?

ADM: The next step of this project will be figuring out how to allow the general public to manipulate their surroundings through smart tech. Heather and I have been very interested in democratizing this tech so that the many can wield it, not just the few. The power of this project is that it is free. We took a technology that is massively expensive to produce and we are giving it away. This is one of the ideas that makes us very dangerous to the status quo. As Amazon and Google fight to buy the advertising space around your head, we are taking this digital landscape and reclaiming it for the people. This tech is a new frontier and it needs to be utilized and built on responsibly. We have used it to tell a story of America that is not skewed by the power structure and is told by the people that have lost and paid the ultimate price. We are dangerous to this system, and this is how I like it. The artist is a threat to the subjugator because we possess the ability to express how others feel in a visceral manner.

Is Mariah a work that you anticipate updating on occasion — new statistics, or as additional information comes to light? Or does it stand to mark a specific moment in time?

ADM: “Mariah” will be roaming the halls of other locations soon (she may even be there). When she moves she will tell the stories of others. Each location will focus on one story at a time. Statistics mean nothing without the stories of the affected being specifically highlighted. If I tell you 200 per day die from overdose in America, this (means little to many people) until the story of one (life lost) brings the number into galvanizing focus. The sad reality is that, for so many (people), they will need to lose someone close to them for them to start to pay attention.

Your brother Joe obviously is mentioned in any discussion of your recent work, including Mariah — but not much about him except for how he died. Can you describe him? What was Joe like?

ADM: He was a good friend. My brother was the funniest person I have ever known and had the quickest of wit … a silver tongue. This could be funny if you were on the right side of this wit or tough if you were on the receiving end. Joey was always there for the people he loved and would give the shirt off his back to a stranger in need. He gave so much of himself away and in the end kept very little for himself. He was sensitive and immensely strong. Joey was a counselor to adults with developmental challenges and he loved the people he was charged to care for. Many of them became part of the DelMarcelle family, coming to holidays and special occasions. My brother was a father and he cared deeply and loved his daughter very much. She reminds me so much of him. I miss him so very much and everything I do with this work is for him.

Top photo: Adam DelMarcelle, left, and Rhonda Lotti, mother of Mariah Lotti, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mariah, DelMarcelle’s augmented reality project at the Met, calls attention to the pharmaceutical money that allowed the Sackler family to become patrons of art while their company’s product led to addiction and, in many cases, death. Photo courtesy Adam DelMarcelle.