Recently, I rewatched one of my favorite Studio Ghibli movies, Only Yesterday. In it, Taeko, a 20-something office worker in Tokyo, takes a vacation to the countryside to work on a farm, all the while recalling episodes from her childhood (or, as she says, being visited by her fifth-grade self). In one memory, Taeko relates her difficulties in learning to divide fractions. She brings home a test with a low grade, so low that her family can’t understand: “No normal kid would ever get a mark this low.” To which their mother responds, “But Taeko’s not a normal kid!” Ouch!

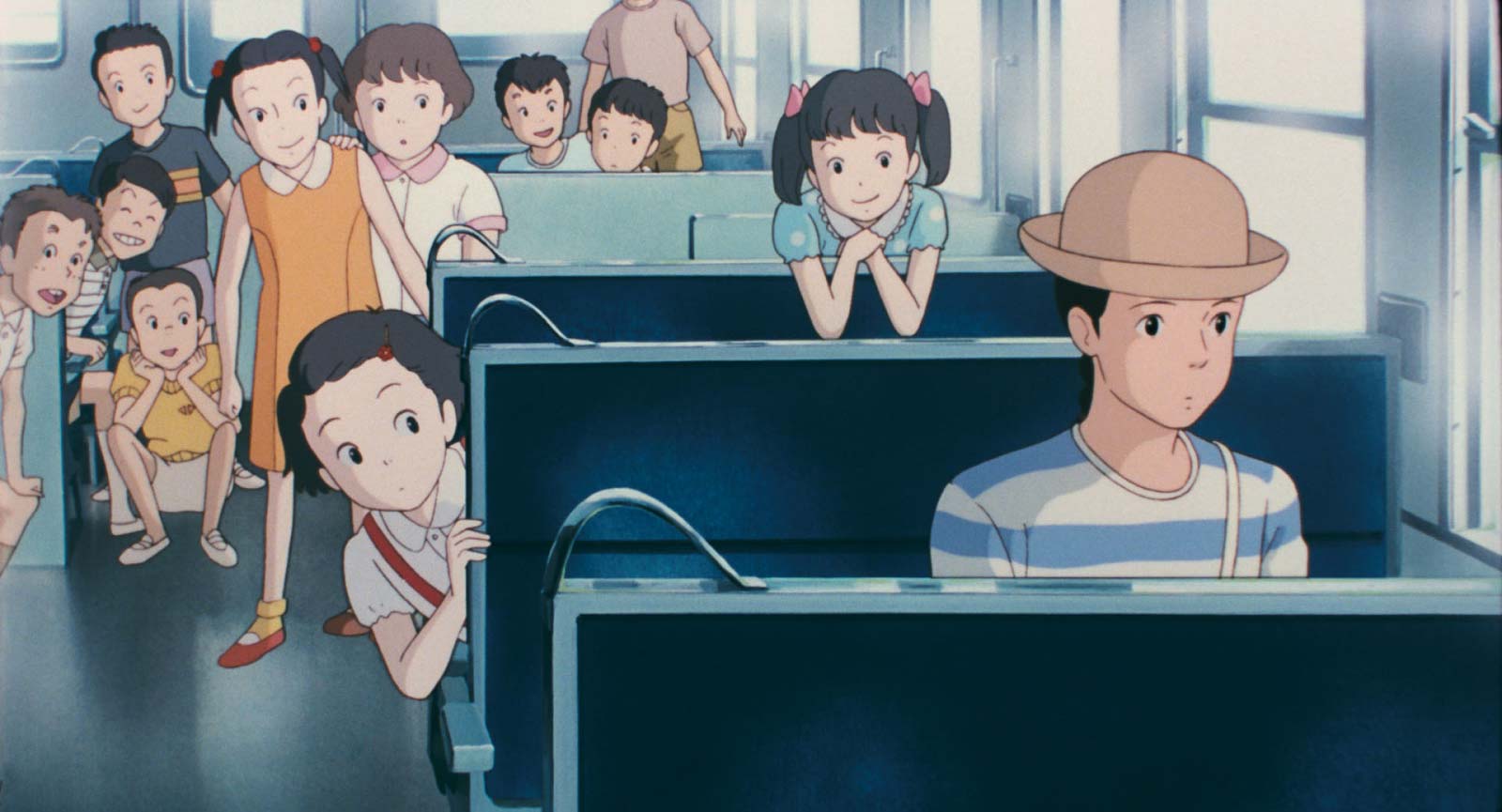

We cut to a scene of Taeko’s sister trying to help her: flip the numerator and the denominator, and then multiply. A single, approved procedure for arriving at the answer. Taeko then asks an innocent question: “Why would anyone want to divide a fraction?!” Taeko proceeds to set up a hypothetical problem: dividing two thirds of an apple by a quarter means… How much apple does each person get? Taeko’s sister is flummoxed, unable to answer the question as posed. “Stop thinking of the apples,” she says.

I’m not suggesting that Taeko doesn’t misunderstand something. I’m suggesting that, in asking an honest question of an otherwise opaque procedure, she is trying to learn. We can work with this. We’re also left with the reality that a small episode can have an outsized influence: we can preach growth mindsets (more on that in a future post…), but research suggests that it’s how we respond in that initial moment of ‘failure’ to understand that can leave an impression.

Recently, anthropologist Susan Blum released a book entitled Schoolishness. In it, she makes a distinction between ‘doing school’ and learning. Flipping the numerator and denominator is a classical example of ‘doing school,’ following the directions without conceptual understanding.

If the remedy to Taeko’s mistake is simply to follow the assigned procedure and get the right answer, she may ‘do school’ more successfully, but we’d be hard-pressed to suggest that she is learning anything but compliance to a rote procedure.

Our students’ mistakes, however confounding, are an invitation to inquire into their thinking, however confounding. I’m in no way suggesting this is easy or doesn’t take patience and take away from other students with their own thoughts, but it’s a small way to center learning in our work that doesn’t involve a brand new system, just a new perspective.