This post was published on the Friday of Labor Day weekend. Having begun as an employee strike day turned holiday to recognize the American labor movement (which, as history reminds us, did negotiate better conditions for many workers and continues these efforts even in the face of rampant union busting tactics…), this blogger hopes you’re reading this after you’ve had a chance to unplug for the long weekend and celebrate the traditional ‘end of summer’ (or at least the end of the season where it’s socially acceptable to wear … shoes without socks?)

As an advocate for evidence-based teaching and learning, I’ve spent a lot of my working life advocating for more student-centered, active, and inclusive approaches to pedagogy. At the same time, I’ve watched as teachers navigated the Covid-19 pandemic, switching back and forth from online to in-person (and back). I’ve seen institutional efforts to promote student success (which are a good thing, don’t get me wrong!) max out faculty already stretched thin, and I’ve seen more discussions of flexibility to accommodate the very everyday challenges that 21st century students face (#adulting). While I am all for these shifts (from focusing on college-ready students to developing ‘student-ready college’), I can also recognize that it has come at a cost to instructor wellbeing.

In a wonderful piece for the Chronicle of Higher Ed, Sarah Rose Cavanagh makes this case and makes it well: a lot was asked of faculty, and all people reach limits. She makes the case that it’s imperative that we balance student well-being with faculty/staff well-being. In other words (also from Sarah Rose Cavanagh): “They need us to be well.” (Link to article). In spite of writing a lot of words about teaching and learning myself, I’ve also become wary of being too prescriptive. If there’s always a new idea, a new term, a new standard, then when do we ever reach a threshold of acceptability? To that end, I want to focus on two resources/ideas that I believe honor the impulse to improve with the acknowledgement of healthy boundaries/limits.

The first of these is a resource called a ‘scope of practice’ (Link to resource). In it, Karen Costa asks us to define our expertise (what are we qualified to do), our responsibilities (what are we expected to do), as well as outlining where we are not qualified or responsible. To learn more, the University of Virginia Center for Teaching Excellence (CTE) has a resource collection in its (quite comprehensive) Teaching Hub (Link to Scope of Practice resources).

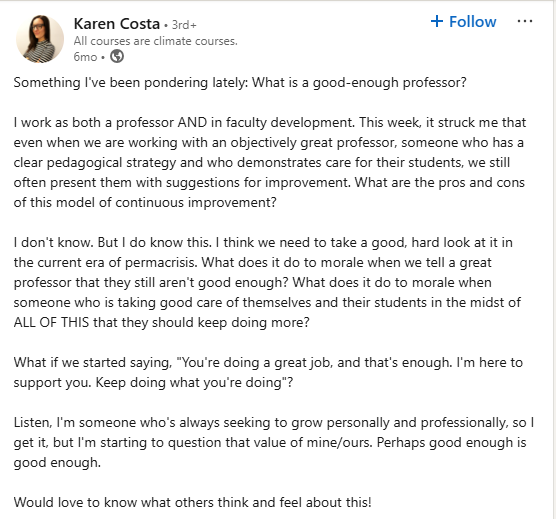

The second idea is the concept of ‘good enough.’ Karen Costa has something to say here as well, with a thoughtful LinkedIn post (that’s not always a contradiction in terms!), posted below: Link to original post

The idea of good-enough sounds like compromise, and, in many ways, it is. Yet, it needn’t be a fatal flaw. It’s often an acknowledgement of balancing multiple priorities as best as we can. To paraphrase pediatrician D.W. Winnicott’s concept of the ‘good enough parent:’

“This [teacher] is good enough not in the sense that they’re adequate or average, but that they manage a difficult task: initiating the student into a course/subject so that they will feel both supported and ready to deal with (inevitable) challenges.”

Whether we’re seeking improvement or looking for an acknowledgment of our ongoing efforts, good-enough has something for you. A colleague of mine handed out buttons at their center that said “Teaching that’s just a little better than it was before we worked together.” That’s the spirit of sustainable improvement, letting alone notions of excellence and seeking out improvement that is meaningful and manageable.

In a follow-up post, we’ll consider how we can honor the labor of learning, by considering where we get our expectations of student ‘work.’