A superhero for all: An interview with Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez, creator of La Borinqueña

Wednesday, February 8th, 2023

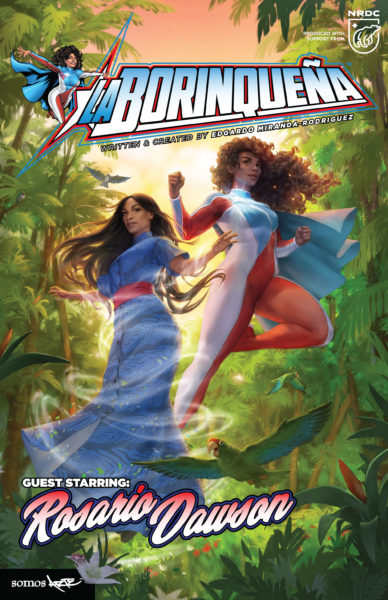

When superhero La Borinqueña was birthed from the imagination of Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez, she wasn’t going to remain “just” a superhero for long.

Instead, Miranda-Rodriguez has fashioned her into a hero whose superpowers of awareness, advocacy, and philanthropy have crossed over into the real world as well. Whether she’s showing up as a powerful representative of Taíno culture or helping to raise money for cultural and environmental causes, La Borinqueña always has a purpose at heart.

Miranda-Rodriguez’s creation has taken the Main Gallery at Pennsylvania College of Art & Design by storm, with Arte de La Borinqueña filling the rooms with digital prints, India-ink drawings, mural photos, graphics, photos and watercolors, action figures, and even a La Borinqueña costume, all work by the artist and his book collaborators.

We asked the artist to talk a bit more about his inspirations, his cultural dedication, and the advocacy tied so strongly to his superhero. Arte de La Borinqueña is on display to the public at PCA&D through Friday, March 10.

So many “traditional” superheroes are not only white, they’re men. It was the default for so long. What inspired you to create Marisol/La Borinqueña as a powerful woman instead?

Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez: I lived in Puerto Rico in my early teens. I recall when I’d get to my uncle’s home, the first thing I’d do was kiss the earth as if I were kissing a grandmother. I’ve always felt a maternal energy from Puerto Rico. I’d learn later that the Taínos, the indigenous people of Puerto Rico as well as Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and the Bahamas believed in a supreme being, a goddess called Atabex. The Taínos referred to their deities as “cemis” and both women and men lead their people as “Caciques,” or chieftains. Personally, I was mentored by women and lived in a single-parent home. I’ve always been aware of the power of women and how Western society has always downplayed, erased, and persecuted women for taking leadership roles. Therefore when I set out to publish this series, La Borinqueña was always going to be a woman whose powers were connected to the feminine energy of the Taínos and the revolutionary women throughout history that fought for social justice.

La Borinqueña incorporates so many elements of Taino culture — How did you, yourself, become aware of this culture? From other interviews (for example, here), it doesn’t sound as if it was always part of your upbringing?

E M-R: I have been reading about Taínos since I was an undergraduate at Colgate University. I still read articles, books, and have conversations with individuals who study Tainidad because I believe that my growth as a storyteller is connected to my growth as a student. The more I learn about my heritage and identity, the more empowered I am to write stories and share them with others.

When you were first designing the character and look of La Borinqueña, were there elements you definitely knew you wanted to incorporate (or, on the other side of the coin, superhero elements you knew would not “fit”?)

E M-R: I looked to two different flags. The first is the present flag of the municipality of Lares, Puerto Rico, which was also the first flag of the short-lived Republic of Puerto Rico from September 23, 1868, created and sewn by Mariana Bracetti, a revolutionary who lead a revolt against the Spanish empire in Puerto Rico. This flag was light blue, red, with a white cross and a white star in the left corner. The second flag is the more common flag of Puerto Rico that was created in Brooklyn, New York, by Mimi Besosa and was officially presented on December 22, 1895, in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City. This original flag was similar to the Lares flag in that it also had a light blue color. I combined both of these flags and similar to the Lares flag with a white cross, I used white piping shooting out of the star to separate the light blue and red areas of the costume. The star is crystal and beveled and part of the mythology that I personally created for the series. I looked at the first iconic superhero, Superman. I stripped his costume of color, and used it as a canvas. I like his costume for La Borinqueña because it was the classic superhero suit and it was not a costume that could be sexualized. Finally, when she is drawn, our artists all know that she will never show off cleavage and always have her drawn in a classic superhero way.

What has been rewarding for you in terms of how La Borinqueña has been received? Have there been challenges to how you wanted this character portrayed?

E M-R: After seven years of publishing La Borinqueña, I’m very happy that we still have an audience that every day continues to grow. Although we have published five books now, our first issue is still our best-selling book across Puerto Rico and the U.S. From primary schools all the way to graduate schools teach and study our graphic novels. What can be challenging is finding the resources to continue self-publishing independently. Our books are supported by our readers and institutions like PCA&D, and we are very grateful for it. We’re still very young in this publishing world. Add to it our philanthropic work, and we’ve created a model that no one else has ever created. We hope to continue this work and inspire new generations with our stories and art.

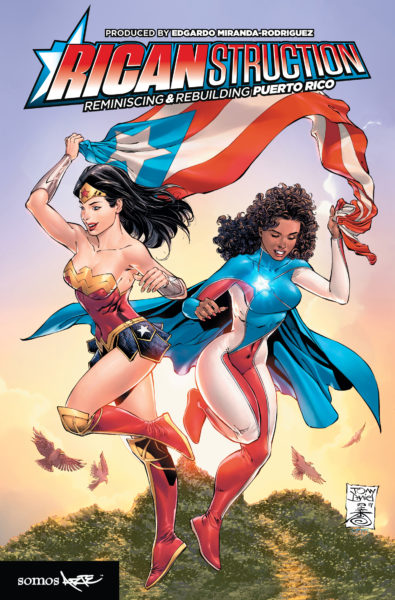

Cover of Ricanstruction, featuring La Borinqueña

Did you envision yourself, as a child, pursuing art and activism as a career? If not, what did you think you’d like to do?

E M-R: As a child, I wanted to make comics. My classmates would hire me to write and draw original stories when I was in primary school and the money I’d make from selling these comic books I’d use to buy books from newsstands. In college, I studied sociology and anthropology then pursued a career as a community organizer. For the last 25 years, I’ve been working for myself via my own studio. I started producing graphic novels in 2013 for clients and soon after saw that I could start doing these with my own characters and stories. I know that the child that’s still part of me is so happy that not only are my stories being read, but that one day soon, action figures will be produced that will be collected and played with based on original characters that I created.

And, finally: What other artists inspire you, if any? Or do your inspirations come from other sources?

E M-R: I find inspiration from many visual artists. Kyung Jeon-Miranda, my partner and wife, introduced me to the world of fine art and the communities that exist within it. Having grown up in New York City, I never visited galleries, only museums occasionally. With her, I’ve learned not only to appreciate so many different artists but different styles as well. Within comics, I’m inspired by the late George Perez, who drew the cover of La Borinqueña #2. I was always his fan, but when I met him and brought him to Puerto Rico for the first time in his professional career, I learned to respect and admire him as a humanitarian who truly believed in charity and sincerely loved his fans. I’m also inspired by artists like my good friend Mike Hawthorne, who is a professor at PCA&D and part of our exhibition. He is one of the celebrated and sought-after artists in the “big 2” (note: DC and Marvel) and to know that he is committed to his family, students, and community is inspiring. I’m very fortunate to have the opportunity to work with so many talented artists who take my ideas and make them into this series, action figures, murals, and costumes all on display.